Underneath the Lintel is a play that, in Diana’s words, “contains the whole universe.” In its hundreds of productions, it has been accused of being anti-Semitic, anti-Christian, pro-Zionist, pro-Christian, and … just weird.

We believe that all of these readings are fundamentally too simplistic for what this play is. If it’s pro anything, it’s pro-human. Pro-curiosity. Pro-adventure. Pro-wonder. Pro-wander. Pro-miracle. It’s anti-surface, anti-quick-judgement, anti-stagnation.

Playwright Glen Berger wrote Underneath the Lintel as he was trying to figure out his own complicated relationship with his Jewish heritage. While it’s a specifically Jewish story, in many ways, it empathizes with all people who find themselves driven from their home through forces of politics, nature, or accidental choice.

We’re providing some dramaturgical resources here to give you a bit more context on the play, and maybe address some questions you might have.

Yours in nerdy research,

Aili and Diana

Warning: This material contains a lot of spoilers. Stop reading if you like surprises and haven’t seen the play yet!

Glen Berger

Glen Berger is an ward-winning, American Jewish playwright. In addition to Underneath the Lintel, he co-wrote the book for Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, Great Men of Science, Nos. 21 & 22, O Lovely Glowworm, On Words and Onwards, and more.

What was Glen Berger trying to do when he wrote this play? Read his Afterword to find out.

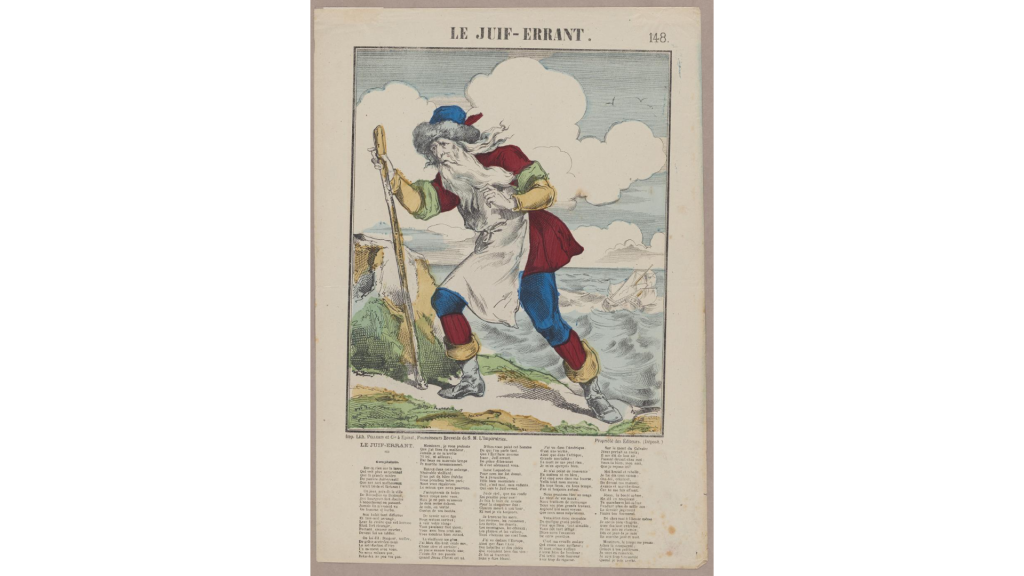

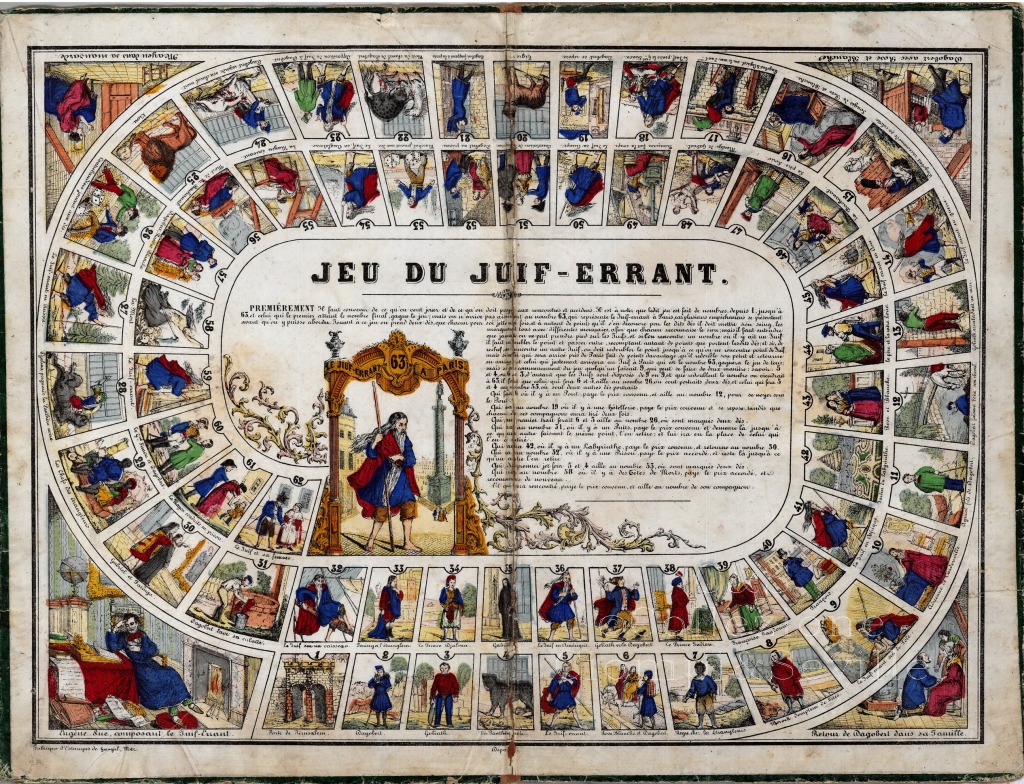

The Wandering Jew

The core of Underneath the Lintel is the legend of the Wandering Jew. First appearing in 13th-century text, the Chronica Majora by Matthew Paris, a monk at the Cathedral and Abbey Church of St. Alban in St. Albans, England, the Wandering Jew tells the story of a man who spurned Jesus and was cursed to wander the Earth until the Second Coming. The original story is indisputably anti-Semitic. It framed Jews as callous and uncharitable in the face of Jesus’ suffering. Well into the 20th century, this story featured in anti-Jewish propaganda, including a Nazi-era film.

Beginning in the 18th century, both Jewish and Christian writers began creating more sympathetic depictions of the Wandering Jew. Poet Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart’s Der ewige Jude (1783) is the first recorded example of the Wanderer having an opportunity to share his side of the story. The Wanderer blames a tyrannical God—pitiless and unforgiving—for his eternal suffering.

Inspired by Schubart’s poem, Percy Bysshe Shelley picked up the theme of the Wandering Jew, reframing him, across nine poems, from “submissive, weak passivity…a new garment of confident, self-assurance. Shelley’s Wandering Jew is now a character questioning the Power that binds him; he is a figure fighting to be set free… it was not the idea of a God that bothered Shelley, but rather the oppression people inflict on other men in the name of that God.” (source)

Jewish writers and thinkers began reclaiming the Wandering Jew as a metaphor for the Jewish diaspora. This legend has been reclaimed in several works of art, including the YA novel The Red Magician, the 1933 film Der Vandernder Yid, several paintings by Marc Chagall, and, of course, Underneath the Lintel.

In recent years, there has been some discussion about renaming the Wandering Jew houseplant to “Wandering Dude,” with mixed results.

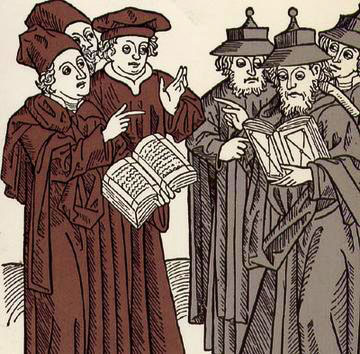

Clothing markers of Judaism

At many points throughout history, Jewish people were required by law to identify themselves by wearing specific articles of clothing. The first example of such a law in Europe came from the 4th Lateran Council, in 1215.

“A yellow, funnel-shaped hat”

Beginning around the 13th century, many countries, including Germany and England, began requiring that Jewish people identify themselves by wearing a funnel-shaped hat, often stipulating that it should be yellow.

Most laws declined to specify details about the form of the hat, so there were various forms of it in circulation. There is some speculation that this requirement to wear a specific hat was a forerunner of the modern yarmulke or kippah.

A Yellow Star or Badge

The practice of requiring Jews to wear a yellow badge on their clothing can be traced back to the 8th century, in the Umayyad Caliphate, when Caliph Umar II required non-Muslims to identify themselves through their clothing, although it wasn’t until the 12th century that yellow badges were specified.

In Europe, the Catholic church required Jewish and Muslim people to identify themselves by wearing various articles of clothing (including the hats described above), beginning in the 13th century. In the 13th century, in France, Spain, England, and Germany, badges, some of them yellow, became the required marker. Most of them were circles or ovals, but in England, they depicted the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments. Jews in Portugal wore red Stars of David beginning in the late 14th Century.

Although the Jewish hats fell out of use around the 1500s, badges were still legally required in some countries through the 18th century.

In the 20th century, Nazi Germany brought back this practice, requiring Jews to wear a yellow Star of David with the word “Juden” on it.

(source)

Locations and significance

In Underneath the Lintel, the Librarian tracks the Wanderer through time and place. Many of the specific places mentioned have significance for real-world Jewish communities and history. Here are the ones we were able to track down:

- Kaifeng, China. Keifeng, in Hunan Province, is home to a large Jewish community, which began during the Song Dynasty (960-1127 C.E.).

- A park bench Stamford, Connecticut gets a passing mention in Underneath the Lintel, but it’s not accidental. Stamford has a “Shabbos park” located between two important synagogues, where families meet on the Sabbath to enjoy restful afternoons together.

- Although Brisbane, Australia, has a fairly small Jewish community, its synagogue is listed on the Queensland Heritage Register because of its architectural and historical importance.

- Zabludow, Poland. Beginning in the late 15th century, Zabludow was a predominantly Jewish town. It was home to a notable wooden synagogue, which was destroyed by the Nazis in 1941. Beginning in 1905, worsening political conditions, including pogroms, led Polish Jews to flee their homes.

One thought on “Underneath the Lintel: Dramaturgical Resources”